Similar to a DJ, I love to take requests for blog

topics. And this week I had several

messages from loyal blog followers asking that I address “Cecil the Lion.” Well, first I had to figure out who Cecil the

Lion was.

Cecil the Lion did not make the news here in

Australia. However, it was the second

most popular Google search topic in the U.S. last week. I read the newspaper articles, watched the YouTube

clips of all the late night hosts, and I have some information you need to know

if you are going to speak intelligently about this situation.

The first thing you need to be familiar with is

CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna

and Flora). If you want to know whether

a fish, bird, animal or plant is in danger and needs protection, you can find

out on the CITES website. CITES

categorizes living fauna or flora into one of three “appendices.”

Appendix 1 is for animals needing the most

protection because they are in danger of becoming extinct. There are about 1,200 species in appendix 1,

including the mountain gorilla, the Asian elephant, and all rhinos. In short, it is illegal to trade in Appendix

1 animals without a licensed permit.

According to CITES regulations, Mozambique is permitted to export 60 lions (as wild-taken trophies) annually so long as the required permits are

obtained.

Most species (about 21,000) are listed in Appendix 2. They aren’t necessarily likely to become

extinct, but may become so in the future if trade in these animals becomes more

popular. Import permits are not required

from CITES for Appendix 2 species, but individual countries may prohibit these

items from being permitted. For

instance, Australia prohibits importation of almost any animal product

regardless of CITES or anything else because we like to control our borders

like Fort Knox. The great white shark

and the American black bear are Appendix 2 species.

There are only about 170 species on Appendix 3. An animal can be listed on Appendix 3 at the

request of any CITES member country because that one country is having trouble

controlling the species. Costa Rica has

placed the two-toed sloth on the CITES Appendix 3 list.

Now that you have some background, let’s talk about

elephants.

In Botswana, elephants are a CITES Appendix 2 animal. That means they are NOT in

danger of extinction. This means that

Botswana has every right to allow hunting of elephants. However, because Botswana likes to play Big

Brother to Africa, and rightfully so, they’ve earned that honour, Botswana

decided to banish elephant hunting 18 months ago. And Botswana is REALLY regretting that decision

right now. Botswana figured if it got

rid of hunting other countries would follow suit. Other countries have not necessarily followed

Botswana’s lead, and there have been some negative repercussions for Botswana

because the elephant population is now exceeding carrying capacity.

Botswana has half the elephant population in Africa,

and one-third of the entire elephant population in the world. Previously, when elephant hunting in Botswana

was allowed it was strictly limited. I

think they only sold about 100 permits a year.

At $100,000 a piece. That’s $10 million

dollars in permits only. Then they also

had to hire guides, hunters, pay for accommodation, transportation, and plenty

of other services while in country. At a

conservative estimate let’s call that $25-30 million in economic impact from

hunters ONLY.

Now, here’s the deal. You can’t just kill one elephant. Elephants understand when one of their herd

dies from natural causes or from an attack by a predator. They do NOT understand when a family member

is killed by a human. Herds are

typically about 30-50 elephants. When

one is killed by a human the rest of the herd goes rogue and can’t deal with

the depression. So, one hunter kills one

elephant (for the permit he purchased) and then the village that is responsible

for that permit kills the rest of the herd.

This is called culling a herd.

This may sound cruel, but it isn’t.

The elephant which the hunter killed, and the rest of the herd, is used

to feed the village for the year. So,

while this is generating a lot of money for the government and the village, it

is also a form of subsistence living.

Back to today.

We have over 200,000 elephants in Botswana. When we used to hunt, we used to eliminate

about 5,000 elephants each year, which helped to control the elephant

population. The population continued to

grow, but not at the fast rate which it grows today because there is no

external method of controlling it.

Adult elephants eat about 300-400 pounds of food a

DAY! And they are herbivores. That means they eat grass. What else in Africa eats grass? Giraffes, zebras, rhinos, impala, and the

vast majority of African wildlife.

Elephants also live to be about 70 and they eventually starve to death

because their teeth wear out and they can’t actually get enough nutrients to

survive. So, in truth, I think killing a

60 year old elephant is actually very humane.

But, back to the food issue. As a

result of the growing elephant population in Botswana other species have

actually decreased in number because they are competing for the same food.

OK, now let’s talk about Cecil. In truth, I find it rather difficult to talk

about the Cecil situation because there has been so much media coverage, and media

is there to sell a story. I’ve read and

hear a lot of conflicting reports, so I think it’s a bit difficult to know the

truth from the fanaticism about this story.

What I will say is that there is a HUGE difference

between poaching and hunting. I actually

just wrote a research article on this topic.

Perhaps I should write a blog post summarising that academic article. The poaching you hear about is normally of

elephants in Kenya and Tanzania. The

poaching that occurs there is truly unfortunate and in most cases the money

earned from these illegal activities is used to support extremist, terrorist

groups.

Hunting in Africa is closely regulated. There are permits that must be obtained,

particular rules that must be followed, and the legal repercussions are worse

than any social ostracism you could possibly experience in the U.S. The locations which permit hunting are highly

dependent on that income and there are strict requirements regarding how the

meat must be utilized.

In short, if the hunt was TRULY illegal then I’m

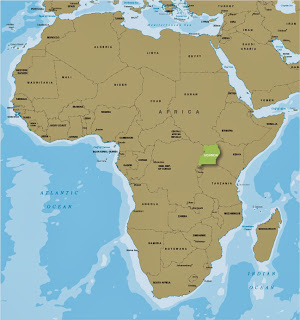

against it. However, Zimbabwe

is no saint. Mugabe’s government has

been corrupt from the beginning, he has been guilty of human rights violations

for years, and he’s starving his people.

The hunters involved in the Cecil situation were thrown in jail, and Zimbabwe’s

call to extradite the dentist is likely an attempt to sensationalize this and

drag the U.S. into negotiations for something.

If the U.S. elects to extradite the American dentist to Zimbabwe it will

be his death sentence.

If you are unfamiliar with Mugabe, this Nando’s (a popular South African fast

food chain) commercial depicts him with Kim Jun Un, Idi Amin, Gaddafi, Saddam

Hussain, and all the other 20th century dictators. The commercial is pretty accurate as Mugabe IS

the last one standing: